Research

Commitment to Research:

The Goa Chitra Museum currently houses more than 4000 individual objects representing the Goan traditional way of life and sustenance. Each of the implements is supported with information obtained in situ while interviewing village elders. Documented oral history and photographic evidence are important research methods used. In our second phase we plan to showcase costumes, jewelry, medical history, traditional toys, furniture, crockery, cutlery, photographs, manuscripts, Art and artifacts. Continuing research and making use of the objects in our collections are fundamental to everything the Museum does.

Partnerships

The Goa Chitra Museum envisages partnerships with other educational entities and scholars, as well as with institutions who share our mission to illuminate cultural diversity and linkages from ancient times to the present, providing a place and context for intellectual exchanges among multiethnic community.

Research papers:

The following articles have been published on the Gomantak Times Weekender Magazine in the weekly column 'Timeless Treasures' by Victor Hugo Gomes.

Tools of the coconut trade 26 April 2009

The coconut oil story 19 April 2009

Three cheers for toddy 12 April 2009

Sweet traditions 29 March 2009

Learning the ropes 22 March 2009

Enriching the future 15 March 2009

Tools of the coconut trade

26 April 2009

The Goa Chitra Museum has been set up in Benaulim, my home village. Every village in Goa had its own forte in the terms of agricultural produce, and Benaulim, besides being known for eccentrics, for unknown reasons, is famous for the quality  of its coconuts and coconut saplings, with very good reason.

of its coconuts and coconut saplings, with very good reason.

In Goa, the cultivation of coconut trees (madd) was deemed most important after rice. Yet today, coconut plantations are greatly neglected (the government estimates for 2001-2002, out of the total area of 36.11 lakh hectares, only 13.93lakh hectares of the area is sown) and as with other agriculture products like food grains, vegetables and milk, Goa is heavily dependent on supplies from outside.

COCONUT HARVESTING

Besides the ghanno (oil grinder), Goa Chitra has a collection of implements used in coconut cultivation and harvesting. There is the koito, a machete used to cut down coconut bunches; the akkaddi/ ankddo, a sheath to hold the koito; the chap/xhap, a hammer with four heads to mark the numbers 2 to 5 on the trunk; the khaddum, a rope harness the coconut plucker wrapped around his feet as a climbing aid; the solod/sonnog, baskets used to collect the harvested coconuts; the rampo/ sullo/sulli/kumbllo, used to de-husk coconuts, and the virlem, a bamboo protective shield for saplings. A coconut plantation is called a bhatt or coconut grove and the coconut grove near the house of the landowner is called ghorbhatt.

All these are becoming rare because our state, which cites swaying coconut trees as one of its selling points, does very little to ensure their survival. Batkars (landlords) no longer seem to care if their yield increases or decreases, being more interested in selling beach front properties on which their coconut trees stand and thus sacrificing a source of revenue that helped sustain many generations of their family, and their

beautiful sprawling mansions, for the gain of just one generation. It was very difficult for me to procure a chap/xhap, which was once integral to the identity of the coconut landlord. The one on display at Goa Chitra was bought from a scrap dealer in Margao.

THE RITUAL

I grew up at a time when the coconut harvest was a ritual. It began early morning with the loud yodelling of an assessor (julgador/oler) to intimate the tenants (mundcars) or the watchman (terlu/tolukkar) to come and be present for the picking. This beginning of the formal procedure woke us up as children. Once all were gathered, the plucker (paddekari/padeli/ padai) would climb the tree by wrapping the khaddum around the trunk and placing his bare feet in it. The khaddum would be raised and lodged in notches cut into the trunk with a koito, giving the paddekar a base to launch himself further up the trunk. While climbing, the koito was held by the akkaddi/ankddo, secured tightly at the waist with a string made from the bark of the kombbio tree. Once at the top, the paddekar would grasp the fronds for support and cut loose the ripe nuts from each side, called dhall and mhall. He would also inspect the crown for insect damage so that necessary measures were taken. However, the local varieties were extremely resistant to disease and had low mortality.

Plucking of coconuts was done four times a year, and the record of each plucking was kept by making incisions katre on the trunk with a koito. The job of the julgador/oler was to state the number of coconuts or bunches missing and assess the number of coconuts that each bunch should have yielded. The account of the missing coconuts was kept on a chuti strip of leaf and immediately settled with the watchman (terlu/tolukkar). His share of the harvest for guarding the coconut trees was balanced against any missing coconuts (dent/selin). The assessor checked the number of bunches on the tree that could be gathered at the next plucking and marked the number on the trunk with the chap/xhap. This helped to check the theft of coconuts.

The harvesters, who were usually women, collected the coconuts in solod/sonnog (cane baskets) and carried them to the warehouse (loja) patio. When the coconuts were to be used, their fibrous husk (sodnna)

would be removed with a de-husker known as rampo/sullo/sulli/kumbllo.

The seeds (biak) were selected from high-yielding stock with desirable traits. The landlord would personally select these seed nuts, which would be of medium-size and nearly spherical in shape. Experiments in producing coconut trees which were large and with good yield were always the pride of the coconut farmer. Baba alias Joao Santan's backyard in Majorda till date is a testimony to such progress. The coconut tree is called kalp-vruksha, a tree that yields everything that one needs from it. It is one of nature's wonder trees, providing nutrition and the raw material for shelter, tools and a wide variety of biodegradable products still largely used in villages of Goa.

PLANTING THE TREE

In the summer, before the rains begin, the bhatkars would dig a pit (lem) for transplanting saplings. The transplantation of the coconut sapling took place when the Hindu star Bharani appeared, between April 24 and May 7, or in August when the mogo star appeared. Once the coconut sapling (kovato) was planted in the lem, it was enclosed in a bamboo enclosure (virlem) to protect it from cattle. A moat (allem/addem) was dug around the root of the coconut sapling to retain water. Once matured, the coconut trees were manured with salt, mud from saline rivers, fish, foliage (sanvoll) and ashes (gobor). Dried up roots were carefully cut or trimmed while clearing the moats, so as to ensure better growth.

Yes, the environment reflects its inhabitants. Look around and it is obvious that the few people who still harvest their coconut plantation know so little of its care. The trees are diseased and it is difficult to get pickers. Our children will never witness the yodeling call of the , julgador/oler; and who cares if the number of coconuts on the trees increases or decreases. The end of the xhap has given us nothing but tender coconuts all along the highways and the beaches. We are after all a thriving economy waiting for the bubble to burst.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

The coconut oil story

19 April 2009

Historical accounts indicate that coconut oil was widely used not only for cooking and lighting lamps, but also as a home remedy for dozens of ailments. Among its numerous medicinal uses is relief of muscular aches and pain, treatment of poisoning and skin infections like scabies, and treatment of ear aches. Massages with coconut oil are a must for new borns in Goa. A telling testimonial to its properties is an account given by George Baldwin, the British Consul General in Egypt, in 1797, "Amazingly not a single person who either traded in coconut oil or extracted it had succumbed to the plague that had killed millions of other victims during four years of epidemic in that country" (Braganza Pereira, 1940).

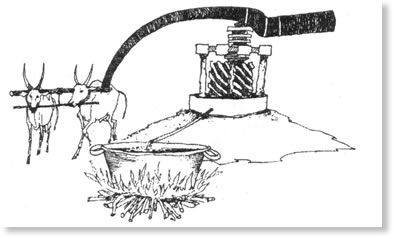

Given its usefulness and the abundance of coconut palms in Goa, it is not surprising that the trade in coconut oil flourished in the state. Until recent times, it was common to see coconuts being dried in the sun in preparation for oil production. In the old days, the oil was extracted from the coconut kernel (khobrem) using a bull-drawn wooden grinder called ghanno.

THE GRIND

The ghanno is an impressive implement, the epitome of skilled craftsmanship and indigenous technology. The main body is a thick column of wood from the jackfruit tree that stands on the ground and has a bowl-shaped depression hollowed out at the top end. This is lined with interlocking pieces of cosumb wood that leave a small hole in the centre for the oil to drain out. The carving of this wood required a special technique that was the proficiency of the Gulab Chari family from Canacona, who would travel from village to village repairing and building ghannes.

The ghanno is an impressive implement, the epitome of skilled craftsmanship and indigenous technology. The main body is a thick column of wood from the jackfruit tree that stands on the ground and has a bowl-shaped depression hollowed out at the top end. This is lined with interlocking pieces of cosumb wood that leave a small hole in the centre for the oil to drain out. The carving of this wood required a special technique that was the proficiency of the Gulab Chari family from Canacona, who would travel from village to village repairing and building ghannes.

A wooden frame called kande is fitted around the upper end of the ghanno. The central arm that serves as a pestle is called the kano and is also made from cosumb wood. One end of the kano sits in the head of the ghanno and the narrowed top end fits into the cup-shaped depression carved into one end of a short teak arm called doulo. The doulo is tied to a revolving frame called cator, made of teak or 'matti' wood, that is fitted around the middle of the main body of the ghanno.

A stone weight, known as bharattar, is used to counterbalances the cator.

To operate the ghanno, a bull is yoked to the cator and driven around it. As the oil is pressed out, it flows through the hole in the head of the ghanno and

out

through the polhe, a spout at the base.

GONE WITHOUT A TRACE?

My first encounter with the ghanno was in 1992, while travelling with a priest in the Pilar-Agassaim area to trace the old Kadamba trading routes (Agassaim was a major port during the Kadamba period, and coconut oil one of the major trading goods of that time). During . our explorations I noticed two huge. round stones that looked like pillars buried in the ground. On enquiring, I was told that these were all that was left of two once fully functioning ghannos.

It took me quite some time to track down a salvageable ghanno. I met ghanekars, the traditional oil . millers, all over Goa, but all of them had discarded their bull-drawn ghannos for mechanised oil mills and no trace was left of the original tool of their

trade.

After much inquiry, I was told that I would

be able to find a ghanno at Agonda. I made the trip there one Sunday morning with my friend Ketan Naik, hoping to meet the ghanekar and persuade him to give me his ghanno for my collection. Although we didn't get the ghanno - it had already been destroyed -- we did find incentive to press on with our quest to preserve what we could of Goan heritage.

When Ketan and I arrived at the ghanekar's home we found that it stood on prime beach property that was being cleared for what looked like commercial development. I asked why, and the ghanekar's tale made me wonder why are politics and politicians so inextricably linked to annihilation of all that is best in our beloved land? It appears the ghanekar had sold his property for a pittance to one of our dear state ministers. Ironically, there was a lot of pride as he explained his aam admi connection.

"My son works for him and is promised a promotion in the government," he said. "The least I can do is let the minister's son, who is studying abroad, satisfy his craving to sit under a coconut tree ana" sip tender coconut water." This, apparently, was what the minister had told the ghanekar was his homesick son's dearest wish!

But the trip wasn't wasted as it gave us another lead that introduced me to Balaji Anand Naik from

Chaudi in Canacona. Naik had just been brought home after a heart bypass operation when I visited him. His ghanno had been completely dismantled years ago and though the various parts were still lying about his compound, they had rotted away while waiting to become part of a bonfire. When he agreed to let me have them, the gratitude and joy was mutual. I had finally found a ghanno I could piece together, while Naik was thrilled that his ghanno would be preserved for posterity. "I'm happy today," he told me as I was leaving with my new treasure. "Before my death, I will see my • ghanno repaired and displayed in a museum."

WORTH THE WAIT

Yes, it took me 14 years to find a ghanno and the best part of another year to figure out how to restore it, but what a majestic implement it was when finally assembled. It wasn't surprising when Bismarck Dias, a former creative head at Lintas who generously offered to support the efforts of Goa Chitra by designing the publicity material, decided to use the ghanno in the museum's logo.

The skills that went into building the ghanno have died without being recorded. To the best of my knowledge, the ghanno at Goa Chitra is the only complete one in existence, another inspiring, yet sad, reminder of the kind of know-how and craftsmanship that once existed in our land.

The ghanno is just one of many fascinating artefacts in the collection at Goa Chitra, all reflecting the accumulated wisdom in agrarian practices, the harmony with the environment, and the rich tradition of tools, arts and crafts of our ancestors. They bring joy to those who value Goan heritage - but also a sense of deep sadness, representing as they do not only how much we have, but also how much has been lost. The museum places this collection in its fullest historical context, integrating art with archaeology with implements from across the generations in the belief that Goa will never move forward until we all fully understand where we have come from.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

Three cheers for toddy

12 April 2009

Toddy tapping - the collection of juice from the bud or spadix of palm tree flowers - has been practised in Southeast Asia for centuries. British explorer Captain Ja mes Cook found the islanders of Sawut in the Indonesian archipelago, tapping toddy from palm trees in 1770, and using it as a drink and an animal feed. It is common in Indonesia as well as Sri Lanka.

mes Cook found the islanders of Sawut in the Indonesian archipelago, tapping toddy from palm trees in 1770, and using it as a drink and an animal feed. It is common in Indonesia as well as Sri Lanka.

In Goa, there are three varieties of toddy: the common one, niro and toddy for jaggery. Niro is purified toddy obtained by cleaning the spadix carefully and sharpening it more than usual. The white liquid that initially collects, tends to be very sweet and non-alcoholic before it is fermented. It is a delicious drink and locally prescribed for the treatment of slight fevers and gonorrhoea.

The toddy for jaggery is sweeter than the common one and collected in damonem which contains some lime. Coconut jaggery

(madanchem goddh is made by evaporating toddy over a slow fire and mixing it with grated coconut. Fresh jaggery boiled in water with a pinch of ginger is a good expectorant.

CHEERS!

Coconut sap begins fermenting immediately after collection, due to natural yeasts in the air (often spurred by residual yeast, left in the collecting container). Within two hours, fermentation yields an aromatic wine of up to 4% alcohol content, mildly intoxicating and sweet. Longer fermentation produces vinegar instead of stronger wine.

Coconut feni, known as launecho soro, is prepared in a distillery called soreachi bhatti. For three days the toddy used to be left to ferment in clay or porcelain pots, called monn or jhallo. It was then boiled in a big earthen pot called bhann with the mouth sealed with

a wooden stopper called mhorannem. The vapours from the bhann passed through a tube called nollo, made from a bonnki stem, and collected in a clay distillation pot called launi, which was placed in an open clay vessel called kodem filled with water. After distillation, the residue, known asgoddo, was removed from the bhann with a spoon called doi or dovlo.

HIGH & DRY

Once drunk widely in Goa and one of the main sources of revenue for the government, launecho soro is no longer produced today. The clay utensils, which added flavour to the liquor, are no longer used. The bhann these days is made of copper. This has affected other trades and, of course, the quality of coconut feni. Potters no longer know the techniques of producing the monn, bhann or launi.

The quality coconut feni of

those days could have been for Goa what tequila is to Mexico. Sadly, as my friend Jess Fernandes states passionately, "Toddy tappers have joined the race to promote Goa as a tourist destination, where coconut trees are cut down for hotel

constructions and their bhattis converted into tourist rooms. Promoting foreign liquors and compromising on the quality of the distillation today with nausaghor, jaggery or battery powder."

It makes me wonder if aleacho, jeeracho, sidracho and dodhshericho soro will one day be known only as terms once used for different flavours of coconut feni.

GLORY DAYS

The toddy-tapping and distillation implements preserved at Goa Chitra are not enough to revive the days of glorious coconut feni. But they are testimony to how, with the transition from traditional learning to textbook knowledge that ignores cultural heritage, the collective wisdom of generation upon generation is quietly slipping away with each person who dies without anyone to pass on the countless secrets of family trades.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

A coconut high.

5 April 2009.

In Goa, toddy (sur), the sap of the coconut tree, is distilled into liquor, made into vinegar or used for  making jaggery. One coconut tree yields about 432 litres of toddy a year, and collecting it was the chief occupation of the Bhandaris, Komarpaik and toddy tapper (Rendeir) communities.

making jaggery. One coconut tree yields about 432 litres of toddy a year, and collecting it was the chief occupation of the Bhandaris, Komarpaik and toddy tapper (Rendeir) communities.

Tapping toddy involves various4 stages and implements. The sap of the coconut palm is collected in an earthen pot called zamono or damonem, which is fitted over the spadix ipoi) that grows out of the base of each coconut leaf. In order to produce toddy, the spadix is tightly bound with a rope (gofe/gophe) made from filaments (vaie) cut with a small knife (piskathi) from the base of the leaf, while remaining attached to the pedicle.

The spadix must then be tapped all around very gently with the handle of the kathi (a flat semi-circular sickle) every alternate day until it becomes round and flexible, a sign that the sap is ready The tip of the spadix is then cut off to let the sap ooze out into the damonem.

Toddy is collected from the damonem in the morning and evening and carried down the tree in a gourd-shaped container called dudhinem before being poured into a clay pot called kollso. The spadix is sharpened at noon by

slicing a small piece horizontally off the top, called cheu, so as to reactivate the flow of sap.

Incidentally, the kathi was sharpened on a plank (follem) of eround wood with marble powder.

PUMPKIN TALES

My collection of toddy-tapping and distillation implements was incomplete since I had trouble tracing a dudhinem, also called dudhkem.

Originally made from a konkan dudhi (sponge gourd), like so many other implements over the years, it has disappeared and been replaced by containers made from non-biodegradable plastic!

I grew up in the neighbourhood of many toddy tappers, but my search for an original dudhinem took me far from home and all along coastal Goa, once the habitat of toddy tappers. No one had preserved a dudhinem nor knew how to make one. This bothered me because it meant that we had lost yet another piece of traditional knowledge. I was finally lucky enough to not only acquire a dudhinem, but also find out how they were made, thanks to an accidental encounter with Baba, a farmer in Sanguem.

I met Baba while documenting a metal-smith's tools in Sanguem, a taluka where many toddy tappers had settled. Agonda is known for the best quality of distillation of palm feni or model.

When Baba showed up to have his plough repaired, I asked him about possibly finding a dudhinem in the area, and he told me of his experience years ago while

ploughing his fields.

"Very often," he said, "my plough would get stuck in gourds that were buried in the fields." By chance I had stumbled upon a trade secret! In the olden days you could tell a toddy tapper's' house by the dudhi creeper growing over the roof or on the matov, a bamboo framework.

It seems that once the 'dudhi' had matured and dried, they were buried in the fields till the inner flesh rotted away and only a hard shell remained - and this was used as the receptacle for toddy.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

Sweet traditions

29 March 2009

Goa Chitra does not contain antiques but artifacts that manifest the social Creativity of skilled groups to contemporary society. Most of the implements at  Goa Chitra have stories woven around them. These are tales of a bygone era. An era when wisdom accumulated over generations was passed on and evolved. Every skill was a specialization with trade secrets and respect!

Goa Chitra have stories woven around them. These are tales of a bygone era. An era when wisdom accumulated over generations was passed on and evolved. Every skill was a specialization with trade secrets and respect!

The Jaggery implements on display at Goa Chitra have one such tale: Once, on my way to Agonda, I met an interesting personality, a 70-plus Amaral Pereira, once a much sought after jaggery producer. He seemed excited with my project and shared with me valuable information. He would go from ushel (sugercane farm) to ushel with his gano (sugarcane grinder), a bodvonno, a heavy wooden hammer used for installing the gano, and other implements used for making jaggery.

They worked on site till the completion of production. Often they would camp on

site. They found indigenous methods to cope with various hazards.

For instance, when there was no crockery, they would take fresh banana leaves, warm them over a fire, then dig a hole in the ground. This pit was layered with these banana leaves and used as a canso (bowl). The pez (rice gruel) or ambil (nachne dish) was eaten from this pit! "

Jaggery production is a lengthy process. Freshly extracted sugarcane juice is filtered and boiled in a wide call, a shallow iron pan. It would be continuously stirred with a dhai (spatula). Simultaneously soda or bhindi juice is added as required.

While boiling, the brownish foam coming on the surface is incessantly removed with a chalno (sieve) to get golden yellow colour of jaggery.

After the juice thickens, it is poured into a bed called van, a shallow square pit lined with lime and rammed with a wooden bat called petni. The thick jaggery paste is

spread with a  small wooden spade called pavdi and after sufficient drying, it is cut into small blocks with the help of a wooden trowel called thappi.

small wooden spade called pavdi and after sufficient drying, it is cut into small blocks with the help of a wooden trowel called thappi.

This van was later replaced by small or medium sized iron or aluminum cans where blocks of jaggery are formed after cooling. The size of the blocks varied from 1 kg to 12kg.

Finally, these blocks were packed in. gunny bags. From 100 kg of sugarcane, approximately 10 kg of jaggery was produced. Getting clean golden yellow ushichem godd (sugarcane jaggery) is an art. .

TRADE SECRETS

Since every occupation was an inherited specialization, most trade secrets were handed over from generation to generation. A trade secret developed over years of working with given material. So what was AmaraTs secret? It is not easy for a man whose livelihood had to be given up for love, to smile so very often, but his eyes sparkled as he said, "While boiling the juice, I would drop a couple of sea shells into

the pan. It helped to draw dirt and brownish foam in one place to make it easier for scooping."

That same year, he lost his wife. An accident before his very eyes took her away. He quit jaggery production. She was his greatest support. The demand for jaggery declined since sugar replaced it.

Simultaneously, most sugarcane farmers fell for a false dream sold to them by the Palmoline lobby. Ushels became Palmoline farms.

Every implement, gano, bodvonno, cail,

dhai, petni, thappi and chalno, now on

display at Goa Chitra has a tale to tell. I saw myriad memories in the tears which trickled down Amarals face, while parting with those implements. I promised him that I would keep his implements and his vast knowledge for posterity as a testimony to the agonies and ecstasies of the simple jaggery producer from Goa.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

Learning the ropes

22 March 2009

While collecting implements and artefacts, I realised I had stumbled upon a treasure of Goan heritage and history My search intensified and as diverse, artefacts were unearthed, I felt the need to restore these tools and instruments as there is a dearth of research on our ancestry. Changes in the Goan economy and society have rendered them obsolete. All this information, knowledge and wisdom of pur ancestors were going unrecorded and hence Goa Chitra came into being..

I was worried about the threat imposed upon these implements. They were being replaced by their more modern and imported counterparts — instruments that were being touted as true depictions of Goan material culture. I consulted elders who were familiar with some of the implements and had actually seen them in use.

These trips also helped to widen and complete my collection, especially of farming and household implements. Our ancestors had a keen knowledge of indigenous materials, and were self sufficient in using materials found within the vicinity of their settlements. Each implement was pre-meditated, keeping in mind the suitability of the substance and its eco-friendliness.

ONE TREE, MANY USES

Most of the ropes used in agriculture had a distinctive feature. They were woven using various natural fibres of trees like kivann, sutachi/redeachi anas (wild pineapple) and a medium-sized evergreen tree known as komai/kombio/ komyo. This tree is found in shady and wet sites near forest streams up to 500 m in elevation. The trunk is often fluted with smooth or rough and scaly bark; the crown is conical with spreading branches and leathery, dark green leaves. The leaves were used to make rain covers called kondo. The

fibre of this tree is soft and cooling and is woven to design ropes for different tasks: shale used by fruit pluckers, davon used during thrashing, cannio used to tie paddy sheaves, davem and zupni used as a halter and collar for animals.

This craft is almost extinct and I was thrilled when one of the Dhangar's demonstrated his skill at making ropes out of these natural fibres.

One theory why kombio and not coconut fibre was used to make ropes could be due to the absence of the coconut tree in these parts. Coconut trees proliferated more along the western coast. Today, this fibre has been replaced by coir made from the coconut tree and more recently, the invasion of plastic culture. The nylon rope has wiped out eco-friendly technology, thanks to hardcore promotions by the nylon lobby.

MUSIC TO ALL EARS

While I was gathering pictorial evidence of the kombio tree in Sanguem taluka, I heard enchanting, soothing music ' wafting from a distance. Some moments in  your life are unforgettable; this was. one such moment. I followed the

sound and was pleasantly surprised at what I saw. A Dhangar named Zumo Dhaku Varak, in his 80s, was gathering his herd, playing on something that looked like a huge upright flute. It is made from a hollow velu bamboo, with a reed made from shirat (a small hollowed bamboo branch). The notes have a calming effect

on the listener. This instrument is known as konpavo and is indigenously designed to calm aggressive/disturbed animals, or to gather in the herd.

your life are unforgettable; this was. one such moment. I followed the

sound and was pleasantly surprised at what I saw. A Dhangar named Zumo Dhaku Varak, in his 80s, was gathering his herd, playing on something that looked like a huge upright flute. It is made from a hollow velu bamboo, with a reed made from shirat (a small hollowed bamboo branch). The notes have a calming effect

on the listener. This instrument is known as konpavo and is indigenously designed to calm aggressive/disturbed animals, or to gather in the herd.

Today, there is a lot of research evidence (Peretti & Kippscludi, 1991) to indicate that certain audio frequencies and sounds affect animal behaviour, something the Dhangars were aware of a long time ago!

This knowledge comes from an understanding of animal behaviour and their sensory perception.

Dhangars were inventors; they tilled, toiled, lived and loved their land, their flock and their materials. Thanks to Zumo Dakhu, the konpavo, davon, cannio, kondo, davem or zupni and shale, are prized pieces on display at Goa Chitra.

But it is all fast dying. What I saw, are perhaps, the last lucky glimpses of the Dhangar way of life. Today their mainstay — cows, buffaloes

and goats — have depleted in numbers. Their grazing grounds are either being cleared for development or have been converted into mines.

A dear friend who visited us at the museum opined that we should not hope to go back in time, instead move into the future. The essence of Goa Chitra is to highlight the wisdom of our ancestors. It's not about retreating, but about using this storehouse of knowledge to answer questions that are of global concern. Consequently, it should lead us towards a healthier lifestyle.

- Victor Hugo Gomes

Enriching the future.

15 March 2009.

This week we begin a series on artifacts from Goa's past. In this first part of the series, Victor H Gomes talks about the genesis of Goa Chitra.

This article is part of a series that will look at the research that went into the creation of Goa Chitra. As a prologue, this is a synopsis of what triggered the creation.

While collecting the agricultural implements that forms the major display at Goa Chitra, I realized that Goans were losing much more than historical artifacts - they were losing evidence of their forefather's lifestyles. Our heritage, not our culture, had a system of self-rule called the gaunkaris, which is believed to have originated in the first century BC. These were primarily agrarian societies. The principal role of these local governing bodies was to maintain and upgrade land quality, protect fishing ponds and waterways, and maintain an intricate system of embankments (bunds) that protected reclaimed land,known as khazans, from inundation by saline tidal waters. This system produced not only an effective means to administer communal lands, but developed an intricate and ecologically sound system of  agriculture. It utilised both fertile and barren lands for the benefit of the people.

agriculture. It utilised both fertile and barren lands for the benefit of the people.

Farming methods were based on the prevailing season and the quality of the soil. Agricultural activities and techniques were adapted to suit the soil, rainfall, level of solar radiation and other elements of nature, a process referred to as gott and loosely translated as 'photoperiodism'.

Farming implements were carefully and intelligently developed to suit soil types, and with a healthy respect for the environment and animals that ensured that the system was sustainable and ecologically sound.

Over the years the Gaunkari institution went through various phases of transition and its evolution in each phase was dependent on the ruler of that time. But never in our history was this system ever tempered with. During the Portuguese colonization, it came to be known as Comunidades.

Being part of this rich heritage, it saddens me that today the Comunidade system is completely undermined. Land conversions, both illegal and legal, have led to large development projects with scant regard for sustainability and severe degradation of the eco-system. Less recognised, but equally devastating, is the loss of hundreds of years of accumulated wisdom in agrarian practices, the rich tradition of implements, tools, arts, crafts and heritage of our ancestors and their sensitivity to the environment.

UNTOLD STORIES

The conception of Goa Chitra is based on many dynamics. One amongst them is my love for Goa. The other is combating daily criticism, whether my investment has been futile. What fuels the project are stories that I encountered while on this sojourn. Each implement has a tale woven with the fabric of our rich history.

On my many visits to Neturli (Netravali), I encountered an implement with the Dhangar community that looked like a sieve. It was beautifully crafted and had seen many years of work. It lay in a corner near the gotli, a fence made from sticks called corvam. I was drawn to it instantly. I wanted to acquire it. Following my gaze, the dhangar Baburam, who was proudly displaying his herd, seemed reluctant to part with it. On inquiry, I learnt that the cane woven basket was known as dhali and was used to heat nachni (millet) during the monsoons. It was kept on a wooden frame called ottu to heat the nachne before processing. This implement was last used in the early 60's.

KUMERI FARMING

Dhangars are nomads, who travelled and camped near hilly areas. They would clear a 50 to 100 sqm patch of natural forest and then, burn it on site to provide natural manure. The land was then cultivated, usually with coarse grains like zonlle and nachne, their staple food, for a period of 1 to 3 years. Then it was abandoned and the cultivators moved on to another patch of forest. They would return to cultivate the same area only after a period of 15 to 20 years, which would give the land sufficient time to regenerate.

This is referred to as kumeri farming. Many of the implements they used for such harvesting were indigenously designed, keeping in mind the land, environment and their animals.

Though the Portuguese wanted to stop this practice in Goa, their policy remained largely on paper as no alternative arrangements were made for the rehabilitation of kumeri cultivators. Kumeri was banned again after Liberation in 1961, but the government then decided to allow the practice in certain areas of forest, because it had no alternative livelihood to offer

the cultivators.

In 1964, the government banned kumeri altogether without making any alternative arrangement. The government felt that such farming was a devastation of the environment and they banned it under anti-deforestation law. The government also felt that in order to protect the environment this land would be best given for mining, making a few people very rich and other miserably poor. Of course, excavations due to mining would mean that there would be less land to protect!

What I saw in Baburam's eyes that day was hope that someday the law may get reverted and they would cultivate again. I travelled back to Neturlim many times before finally convincing Baburam to sell me his implement only with a promise that if ever he needed the implement, it would be immediately returned to him. Incidentally nachne is no longer cultivated in Goa and what is available in the market, today, comes from outside the state, grown with chemical fertilizers.

- Victor Hugo Gomes